object permanence

2025

Object permanence is knowing something exists without being able to see it. Babies are born without the ability to understand a ball is still there even when a blanket is draped over it. Out of sight, out of mind. As we grow, we learn that even though we can’t see the ball, it is of course still there.

Certain environmental problems are extremely visible, from islands of plastic floating in the ocean to the smoke of wildfires obscuring the skies. But many are not. They travel invisibly through waterways, in the air, up the arteries of trees, and through the soil. Of course, we humans have caused the problems. We use and throw PFAS-laden chemicals down the drain. We allow our septic systems to overflow, leading to watershed nutrient overloading. We bring home microscopic invasive species from other parts of the world that cause ecosystem-wide destruction.

It is these threats: threats to our health, to our biodiversity, to our ecosystem resilience, that are calling for immediate attention and action. But without visibility, we lack connection to these crises and often forget about them entirely.

Sarah uses the lens of printmaking to explore this concept of invisibility and how visibility can lead to connection. From the existence of the forever chemical PFAS in the soil, to nutrient overloading in the Great Bay estuary leading to eelgrass decline, to the intensive root systems of invasive plants, to the invisible destruction of the beech tree population by an invading nematode—these are all issues that her woodcuts address. By incorporating monoprinting techniques with her more traditional woodcut practice, from stenciling to selective ink rolling, her prints reveal the invisible layers underneath.

Underground fortress

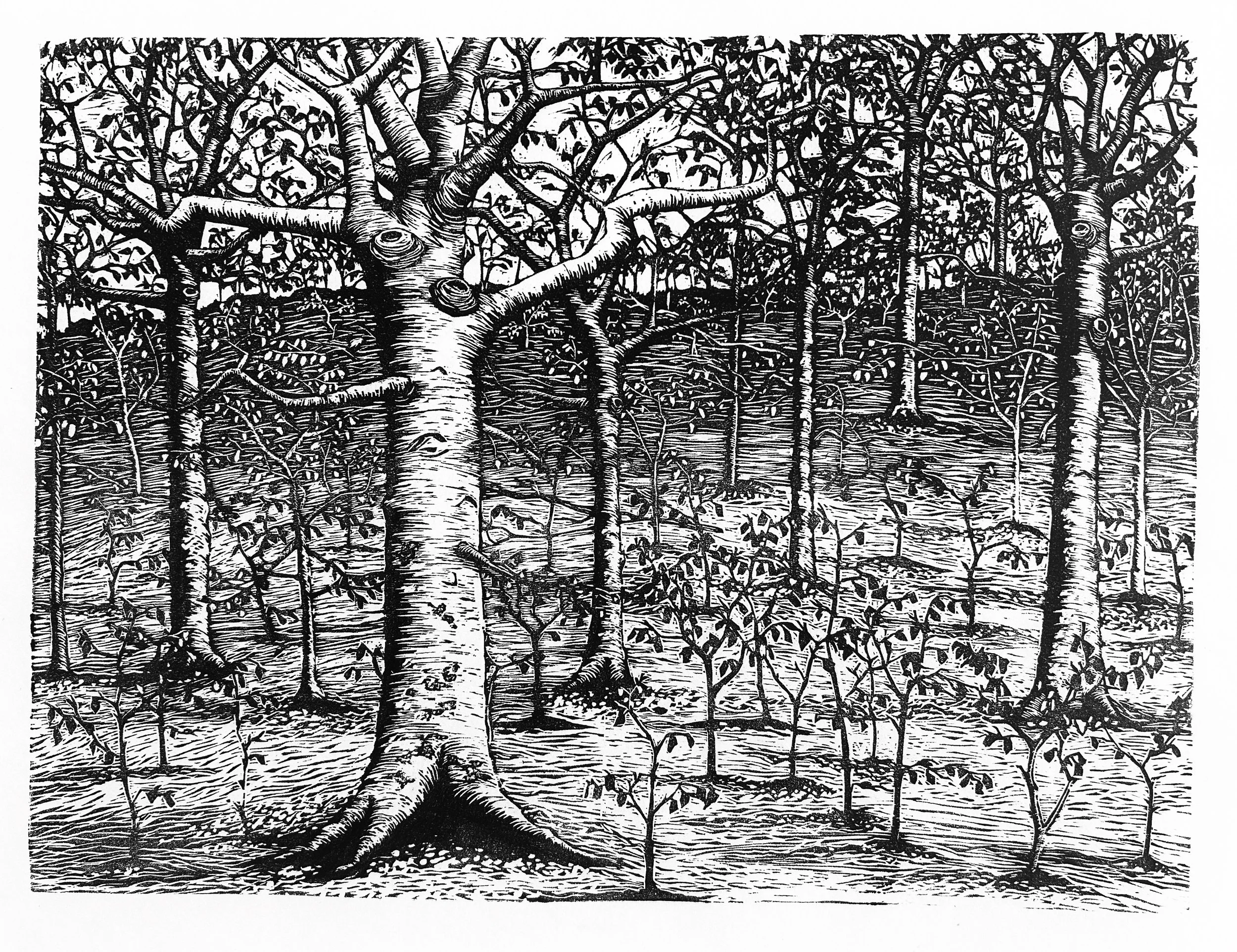

Beech trees are a staple in the New England forest, ecologically and culturally. But beeches are facing a great danger, and very few are talking about it.

Everywhere I looked this summer, beech leaves were striped. This wasn’t due to seasonal change but rather a nematode causing beech leaf disease. The disease was found in Ohio in 2012 and has since spread into New England. Infection means likely death, and nearly all the trees in my forest are infected.

Invasive species like this roundworm, originating in Japan, are causing untold damage to our natural world. A warming climate and lack of education and funding spread them faster than we can keep up with. A beech tree die-off will affect entire ecosystems. What will our forests look like without the stately beech?

Beech earns its stripes

The effects of Teflon Culture

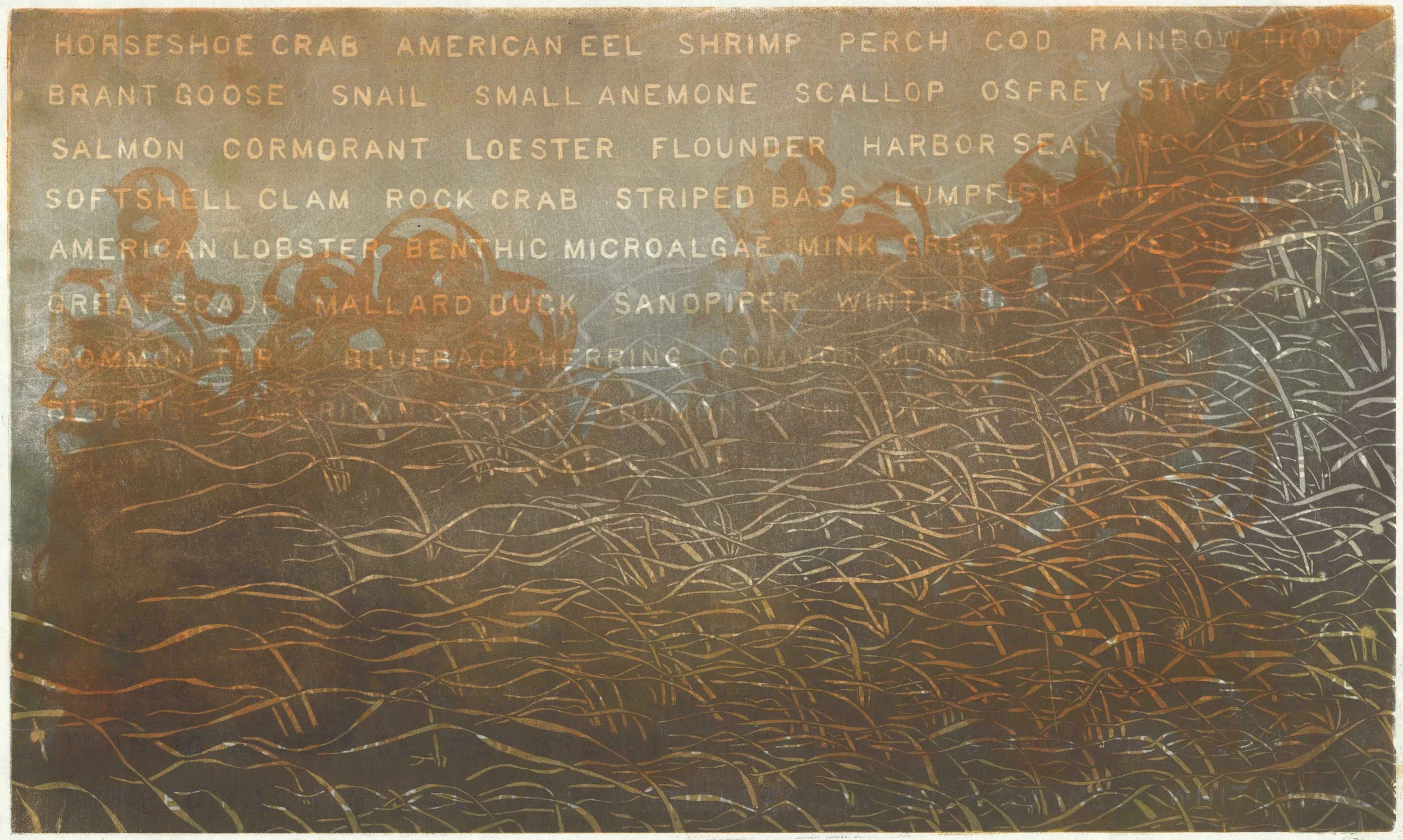

One of the most significant ecological challenges facing the Great Bay Estuary is nutrient overloading. Nitrogen/phosphate run into the bay from runoff, fertilizers, poor septic systems, among other sources, and causes algae to bloom in great numbers. The algae blooms cut off sunlight to the bottom of the shallow waters, which prevents certain plants from receiving the sunlight they need to grow. Eelgrass is one of those plants. This is a problem because eelgrass is a keystone species, which means it holds the ecosystem together. It provides habitat and forage and safety for a number of species, habitat for fisheries and is a source of blue carbon (aka: sequesters carbon in the ocean). So eelgrass is extremely important, and it is also facing a huge decline—not just here in New England, but around the globe.

This woodcut was printed with two blocks and a stencil. One of the blocks lists just some of the many species that rely on eelgrass, while the other portrays the humble grass itself.

Dutch elm

Ash borer

Wooly adelgid

Japanese knotweed is known to be a terribly invasive plant: a plant that can grow into houses and send roots down rivers to colonize riverbanks. The reason why it is so difficult to kill off is its underground root system. The roots form a dense mat underground, making it impossible for other, particularly native, plants to grow in a knotweed colony. I wanted this piece show how complex and aggressive this underground system really is. This piece was made with three blocks, one printed in a reduction style for above-ground matter and two blocks solely portraying roots.

Mother beech

In 2020, a young organic vegetable farm family had their farm tested for a relatively newly discovered chemical called PFAS. What they found, which was shockingly high levels of this forever chemical in their soil and even in the lettuce itself—caused their farm to shut down and brought the issue of PFAS pollution to the public awareness.

*PFAS is found in many places, from firefighting foams to waterproof food containers to Teflon dishes to soaps and cleaning products— In the case of Songbird Farm in Maine, it came from the use over many years of municipal sludge spread over the fields as a fertilizer, before this farm family came to even own the land. This is one of those ecological and health crises that we are finding to be quite literally everywhere, and the breadth and scope of its effects are still not yet known.

But it’s invisible.

This piece was made with three woodblocks. One block portrayed the PFAS chemical structure, and I printed it over and over in various colors and with selective inking, to ensure the PFAS was in every blade of grass, every teaspoon of soil, every leaf of lettuce.

The Decline of Eelgrass

Elm trees used to line city streets, which is why we have so many roads named Elm Street. But years ago, dutch elm disease was introduced in the US and elm trees started dying off en masse. The disease is spread by a beetle, which burrows under the bark of the tree in intricate patterns.

It is difficult to find a true American Elm these days, but luckily we still do have elm trees in the form of disease resistant hybrids like Liberty Elms.

This piece was made from three woodblocks and stencils. The first woodblock depicts the pattern that the beetle makes under the bark of the elm. The second is the texture of the bark of the elm, made by a rubbing. And the third is a silhouette of an elm, a characteristic umbrella shaped profile. These blocks were printed together in a monoprint technique, over and over again, in varying directions and with selective inking. Stencils of toothed elm leaves were also inked and printed.

A beautiful, iridescent beetle lays its eggs in the deep recesses of the ash tree bark. Eggs hatch into larvae, which burrow under the bark and dig squiggly s-shaped tunnels as they feed on tree tissue. Larvae then emerge from the tree as adults, mate, and the cycle repeats. Within a few years, this little green beetle will kill an entire ash tree.

Ash trees are so important ecologically because they grow fast, they’re often the first to repopulate after a forest has been disturbed, and they are very adaptable. We highly value ash wood, which is used for making baseball bats, furniture, flooring, and tool handles.

It’s hard to imagine looking around an eastern US forest and not seeing ash trees everywhere. But the emerald ash borer, that invasive green beetle from Asia, is single-handedly taking down the US population of ash trees, and we aren’t able to stop it fast enough.

But: you can help to prevent the spread of Emerald Ash borer and other invasive pests. Do not bring firewood from place to place; buy kiln-dried firewood. If you notice signs of the borer, you can contact the USDA Emerald Ash borer hotline at 1-866-322-4512.

White fuzz. This is the reason why we’re seeing fewer and fewer eastern hemlock trees, and this is what forest ecologists are so scared of. Tiny white cotton balls found at the base of hemlock needles indicate the eggs of the hemlock wooly adelgid. An invading insect unknowingly brought over from Japan in the 50s, these tiny bugs suck the tree’s sap, reproduce, and can kill the tree outright within 3-5 years.

With no natural predators here, adelgids are decimating hemlock stands. In the Smoky Mountains and areas south, dead hemlock groves are everywhere. We still have plenty up here in New England, but the adelgid is on the hunt and will continue to destroy this keystone species unless we intervene.

Reclaimed I and II

Past land use is a mostly invisible element that hugely affects the ecosystem and the health of the soil and water. This piece was made after a residency in the foothills of Appalachia, where wild medicinal herbs are native and biodiversity is high. Several decades ago, this land was strip mined. But thanks to a long-term land conservation project called United Plant Savers that saved the land 50 years ago, the land was reclaimed. Now species like slippery elm, sassafras, black cohosh, American ginseng, and goldenseal (among so many others) are able to flourish, supporting a diverse ecosystem.

This diptych was made using three woodblocks and a reduction technique. The bountiful prairie grasses print is the present day ecosystem. These blocks were then used to create a dark abstract version, and I carved a third block based on what I imagined the strip mine looked like, and printed it on silk tissue overlaying the abstract print. Past and present.

It’s all in the packaging I, II, and III

I am so frustrated by the amount of plastic waste that comes out of my kitchen every day. So much of my produce comes in plastic mesh bags; in fact nearly every item I buy from the grocery store comes in packaging to be sent to a landfill. I saved up some of this waste and used it to create monoprints. These monoprints are layered over 2-block woodcuts of seaweed. So much of our plastic waste ends up in the ocean, not simply as piles of trash but broken-down microplastic, which, we are finding out, is everywhere. There has to be a better way to package food.